How do we want to learn together on this land?

Outdoor learning and exposure to nature supports curiosity, creativity, and is generally regarded to be fundamental to child development (Grimwood, Gordon, & Stevens, 2017; Chawla, 2015). Despite these benefits, land-based learning remains on the periphery of curricular foci and is typically limited to sporadic experiences that are disconnected from student curriculum and teacher pedagogy. More accurately, taking students outside is often used as an incentive or a bonus activity for children once the more important classwork is completed.

How schools ask students to think (or not think) about nature is problematic too. Sobel (2008) shares the story of Bill Bigelow who describes his relationship with nature in school: “We actively learned to not-think about the earth, about that place where we were. We could have been anywhere — or nowhere. Teachers made no effort to incorporate our vast, if immature, knowledge of the land into the curriculum” (p. 2). On the other hand, when we do think about nature in school, I have often observed (and participated) in what Sobel (1996) terms “premature abstraction,” the out-of-sync process of introducing global crises such as mass extinction or the climate emergency before students are developmentally ready for these topics. When they are introduced at the wrong time they can “create anxiety, fear, and hopelessness in learners that makes them less capable of taking socially or ecologically appropriate action” (Gruenewald, 2003, p. 7). Despite the recognition that students need to feel an affinity with their natural environment before they should explore these crises, the crises are high-interest provocations that educators regularly use as an entry point into environmental education (Egan and Blenkinsop, 2009; Corcoran, 1999, as cited in Moroye, 2017; Gruenwald, 2003; Sobel, 1996). As Egan and Blenkinsop (2009) suggest, this may be a reflection of environmental education being incongruent with the general education theory of assessment. It is difficult, for example, to assess the development of environmental values, whereas it is much easier to assess a report (or even a proposed solution) on an element of the climate crisis.

Knowledge without love will not stick. But if love comes first, knowledge is sure to follow (Sobel, 2008, pp.12-13)

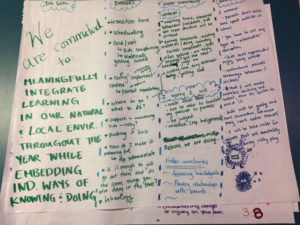

Last year, a colleague and I began exploring how we can move First Peoples’ Principles of Learning from practice into meaningful pedagogy using a land-based approach. We had a hunch that land-based learning where students routinely go outside represents a potential high-leverage pedagogy that will affect student achievement, social-emotional and physical well-being, and understandings of environmental stewardship. We used the Spirals of Inquiry approach to scan our students and engage our families in conversations about outdoor experiences and local knowledge. We noticed there was a gap between families and students when it came to thinking about and communicating significant learning stories around our theme of nature connectedness and FPPL. We brought this to our staff, and facilitated a discussion around our own assumptions about taking learning outdoors and using FPPL as a framework to guide instructional decisions. We committed to testing our assumptions through the implementation of three core routines – sit spots, story of the day, and reflective journaling/sketching. Our next steps are to set the conditions and create the space for these routines in the upcoming school year, and reflect on how these experiences might challenge some of our deeply rooted assumptions about education.

Here’s the rub.

While there are a number of studies that outline the benefits of routine exposure to nature for both children and adults, and in the conversations we’ve had with adults at our school they clearly articulate significant memories of learning experiences in nature and believe their children should be outside more, we tend to stop taking students outside to learn after the earlier primary grades. Why? I would like to invite teachers, educational stakeholders, and parents to have this conversation. I suspect it begins with what we believe learning to be. Using questions inspired by Madjidi and Restoule’s (2008) comparative study on Western and Indigenous epistemologies, we will explore:

- What is learning?

- Where do people go to learn?

- How do people learn?

- Who (or what) do they learn from?

- Why and for what purpose do they learn?

This inquiry matters for students because the significant adults in their lives are partners in their learning. It provides an opportunity to extend what we define as “school” and an “education” to include the people who students spend most of their time with outside of school. Knowing that “younger people model what older people do, makes it imperative that grown-ups make nature connection a priority in their lives as well” (Young, Haas, and McGown, 2016, p. 8). So the intention of the inquiry is twofold: to support students in getting outdoors and to build a greater community of support to come alongside students. We will wonder:

How do we want to learn together on this land?

There is a diverse range of prefabricated nature-based programs that seek to expose children to nature and outdoor learning, and I think in our inquiry it is important to not align too closely with just one program. The expectation as we explore what learning is in our community, is to develop practices that are specific to our social context and our local environment. A land-based approach that is informed by Indigenous ways of knowing and doing is probably about as specific as we would want to be from the outset. Important in such an approach is the primacy of place and context, and how individuals willingly engage in relating to the space and others who occupy it. This connection to land and others reinforces the notion that “a sense of belonging to a specific, localized community is one of the most profound sources of human identity” (Fettes & Judson, 2011). Not only is place-making, or engaging with the land, a major component of land-based learning, but so too is acknowledging the ancestry of the land and honouring the knowledge of the Indigenous Peoples there. From an educational perspective, this represents a fundamental shift from knowing the land to relating to the land (Grimwood et al., 2017). The Forest and Nature School in Canada (2014) captures the same idea when it advocates for developing “a sense of ‘heart knowledge,’ which helps children tread the landscape – figuratively and literally – moving from ‘I know’ to ‘I care’” (Forest and Nature School in Canada, 2014).