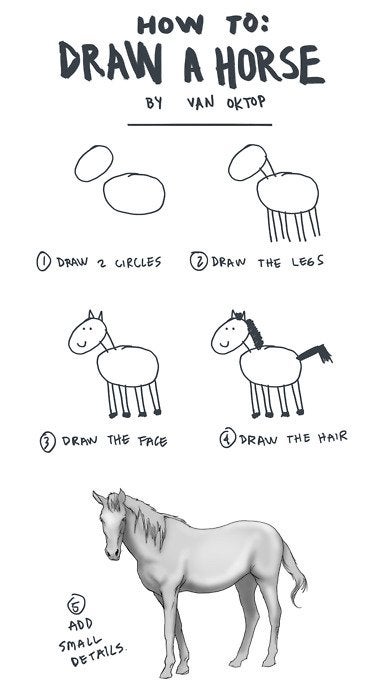

Prior to this course, my knowledge of inquiry was informed by a handful of professional development workshops put on by my district and trial and error inquiry-based learning sequences put on by me in my classroom. In theory I knew the process and I knew the buzzwords, but there always seemed to be a bit of a disconnect between my lived experiences of inquiry and the student stories shared by keynotes at the workshops. I could follow along in the process up to a point, and struggled in the final steps. It felt similar to the steps in this picture:

What were the small details that I was missing?

Inquiry as I knew it was based on the idea that learning should be learner-centered. I now think we were confusing inquiry-based learning with discovery learning. Discovery learning is characterized by minimal student guidance and teacher instruction, and has limited education value. It assumes “that learner-centered pedagogies should be synonymous with learner-directed approaches” (Scott, Smith, Chu, and Friesen, 2018, p. 44). Although well intentioned, my role as educator was preparing engaging provocations (edu-tainment), documenting student voices, and hoping that these quasi-connected elements would add up to some sort of deep learning for students. It was with some unease that I engaged our students in inquiry-based learning – not because I believed in efficacy, but because it was what the district valued for learning.

What this course has offered was the research and confidence to articulate why educators should be engaging their students in inquiry and the framework in which to launch a rigorous inquiry. One of the changes to my thinking was around the belief that inquiry must be learner-directed. Instead, rigorous inquiry includes direct instruction and extends from traditional instruction additional ways to support learners through a broader repertoire of instructional practices (Scott et al., 2018). Students still learn from sensory experiences, from each other, and from introspection, but it is with more intentionality that teachers scaffold these experiences to facilitate deeper learning. The role of the teacher, then, is fluid and moves from mini-lectures to facilitating whole group discussions, to researcher, to observer, and so on. They are trying to ensure everyone has the opportunity to share, synthesize information, and try to make connections back to the essential questions.

Another shift away from inquiry as a purely student-driven process has been in how we privilege student questions. Clifford and Marinucci (2008) “highlight the need for teachers to avoid privileging the questions and interests of students simply because they come from the students themselves, as this ‘can quickly degenerate into sentimental practice that shies away from thorny conversations about whether mistakes are being made or misconceptions overlooked’” (p. 683 in Scott et al., 2018, p. 45). I feel slightly abashed to admit that this is something we’ve done in our inquiry cycles in the past. We honoured student voices as they contributed questions and knowledge, and we did the heavy lifting of making the connections to our essential questions rather than pushing the student to make the connections on their own. One of the hardest lessons I have learned this school year as an educator is around enabling constraints, which is exploring how I can do what I want to do within a confined parametrer. I feel this is something practical, and something we should be making explicit to students in our inquiries.

I now distinguish between an “education” and “learning.” I believe an education is something that happens to us and that is directed or guided from the top down. It doesn’t always follow that this process is merely the transmission of knowledge and that we aren’t acquiring critical skills, but this process is always chosen for us.

Learning is different from education in that I own it. I think praxis lives in the learning process. When I think of learning, what immediately comes to mind is one of the First Peoples’ Principles of Learning: “Learning involves patience and time” (FNESC, 2007). This means that learning doesn’t follow an 8:30-2:30 or a semester schedule! Some of the most meaningful learning I have done in the past couple of years has been around topics I’m particularly passionate about with a small group of people who are interested in the same thing. It is powerful because we chose the topic, we made the schedule, and we set the conditions.

The lifewide nature of learning has always been something I have valued and tried to include in my curricular designs, and this course has really provided me with the theoretical underpinnings for the continued inclusion of teaching and learning in and with the community. This begins with recognising the variety in societal tasks and work, and acknowledging that schools traditionally offer a limited array of programs, and even fewer that are valued as core subjects. Friesen (2009) articulated a similar sentiment when she shared that “so little of what [students] learn outside the school has any place inside the classroom, many discount what they learn each day about how to function at work, in shops, and with each other…Learning has been reduced to what they do in school. Living is what they do in the real world” (p. 93) Instead, I believe that inquiry offers a more holistic approach to education that honours the strengths and aspirations of learners. It aligns with First Peoples’ Principles of Learning and knowing that the more we diversify opportunities for learners and increase our instructional repertoires as teachers, the more equitable our system can become.